Works

FORBIDDEN!

2010

The series of photos FORBIDDEN! was prepared over several years. While travelling Pawel Kowalewski took various photographs of different signs with orders and injunctions and on their basis made reproductions. They were presented for the first time at the 2 Mediations Biennale in Poznań in 2010. The main sign for the Biennale itself was one of the photos from the series, with the message “Europeans Only” printed on a large format banner.

Descriptions to accompany Pawel Kowalewski’s lightboxes:

Do Not Rush

Tokyo, 2011

Tokio, two months before the tsunami. This sign is so exotic for a western civilization – Do Not Rush!

When I witnessed the stoical calm inside the heads of my Japanese friends, who we were caring for I was reminded of this notice. How much can a man learn by taking each step carefully, thoughtfully and without haste? Great are the positive outcomes that such an approach can lead to.

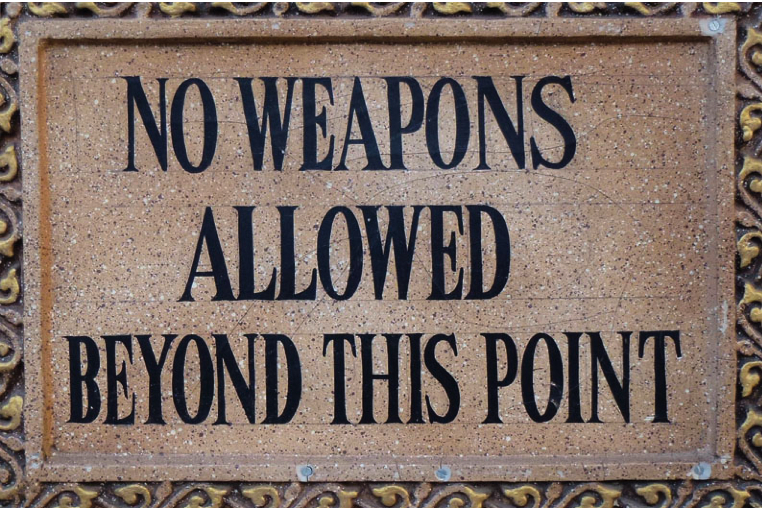

No Weapons Allowed

New Delhi, 2011

New Delhi. Entrance to the Kingdom of Dreams, where glitzy bollywood shows take place.

The Kingdom of Dreams has recently opened in the capital of the country with the fastest growing economy in Asia. The economy is growing so fast in fact that slums surround the Kingdom of Dreams and people sleep on the streets. This is probably why one shouldn’t enter the Kingdom of Dreams with a weapon.

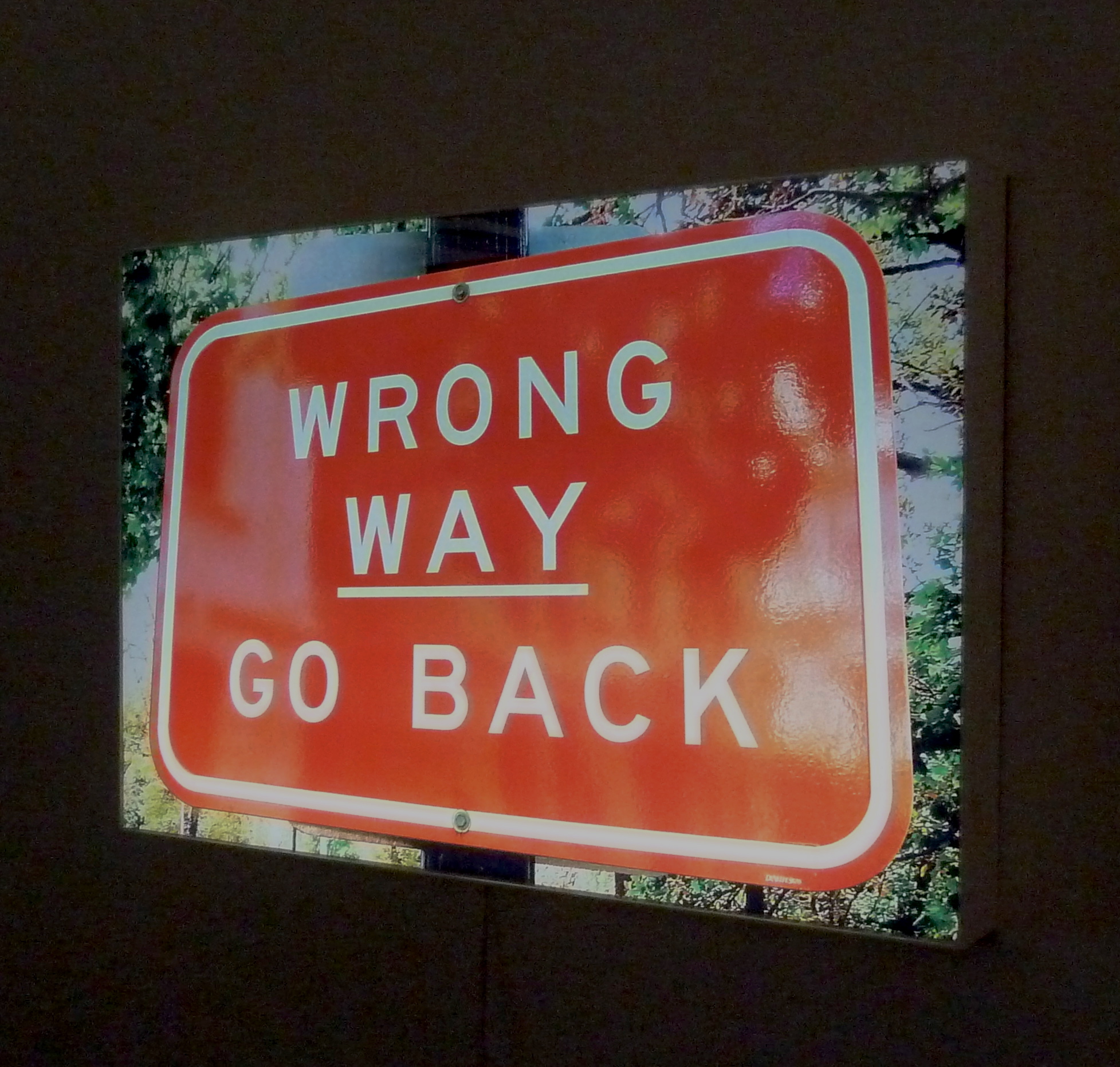

Wrong Way, Go Back

Melbourne, 2009

Melbourne, the capital of Victoria State in Australia. The old British penal colony for thieves and prostitutes. The history of Australia is in these 4 words – Wrong Way. Go Back. One can always turn back from a badly chosen path.

It was thanks to Memento that after the gold rushes, persecution of Aborigines and detention of immigrants in tin barracks, that this country while at the height of its extraordinary development had the courage to apologise to its native citizens for the crimes which were committed against them. Up until the 1970s the Aborigines had been treated like second class citizens with the taking of their children, forced sterilization, confiscation of their lands and general brutal treatment and discrimination being every day occurrences.

Australia in a fairly short time turned away from this path. The words “Wrong Way. Go back” however do not only refer to this country. There is always time for each of us to turn back from a badly chosen path.

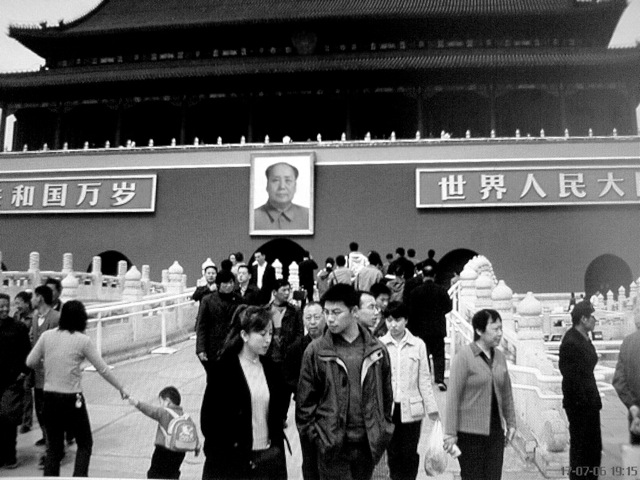

Europeans Only

Johannesburg, 2007

The text “Europeans only”, is a symbol of the system which divided people based on their race and the colour of their skin.

Opened in 2001 in Johannesburg, the Museum of Apartheid was created so as to document the XXth century history of Southern Africa in which apartheid played such a central role. Racial segregation in 2001 seemed to be something which had disappeared in the mists of the previous century.

• 2010 – France deported a Romanian citizen of gypsy origin…

• 2011 – Death squads murder foreigners in Germany…

• 2012 – Dutch authorities encourage citizens to report foreigners…

This is the 2012 context for this museum notice from Pretoria station…

Totalitarianism Simulator

2012

The Totalitarianism Simulator is a real experiment based on the theory of the famous Italian philosopher, Giorgio Agambena. This thinker believed that the legal and ethical system of the concentration camp is still the dominant paradigm in modern society and that in fact we have never left Auschwitz, and that we still organise the modern world in the spirit of totalitarian systems.

Images of genocide, death and various other forms of evil that occur every day in the world, reach us using the same channels and the same ways as all other media messages. The only question is – how do we react? Pawel Kowalewski places us face to face with a terrifying system. By taking part in an experiment which we undergo in isolation in a closed cabin, the artist wishes to awaken our awareness of our unplanned but nevertheless present complicity. In the simulator he uses the experiences and principles, which were first formed in the Gruppa manifesto a quarter of a century ago. Even though Gruppa was just an informal association of a few artists, their words still remain strangely appropriate today. “We start in times where everything is defined, there are no connotations. Everything swims in a puddle. Everything’s allowed because nothing means anything anymore. That’s why we want to name things in a direct and straight way in the language of painting, to find solid ground without turning.” Kowalewski has found his contemporary ground, and to do so has reached for the world of media.

For several years he collected images on the internet, carefully choosing, processing and arranging them. The presented “dogs of war” – death, hunger and conflagration are in fact the results of fascism, Stalinism and other “isms”. We don’t recognise the moments or the victims of murders, shootings and rapes. What’s important is that the artist chooses them so that they together become one loud shout of protest. These images are confronted by others which portray an idealised, even joyous, life which carried on and still carries on often just beside the horrors. The photographs mix together, forming a collage of violence which is then completed by a live register of the faces of the unaware viewers of the projection. Thus the viewer himself cannot help but become part of the whole process.

Taking up the main space in the exhibition, the Totalitarianism Simulator itself is an inhuman machine soullessly grinding the everyday world.

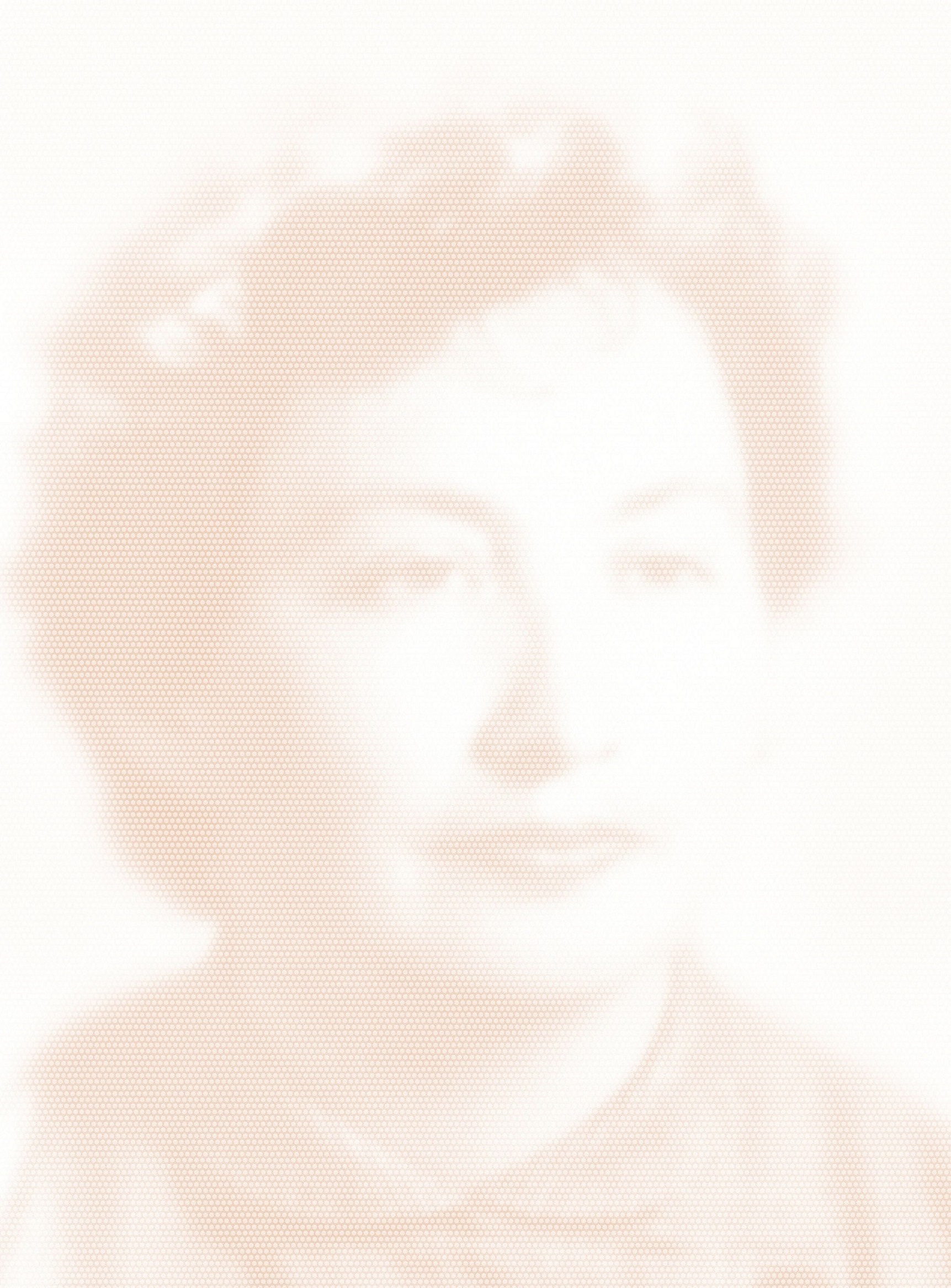

Strength and Beauty

2015

Strength and Beauty. A very subjective history of Polish mothers is a form of tribute to the young women who were born at the beginning of the XXth century, and whose youth fell during the time of the Second World War and the development of the two biggest totalitarian systems.

The project consists of large sized portraits (200x140cm) based on archive photographs of the heroines. The graphics, created in a monochromatic style, are made from small dots which form a whole only from a certain distance. They use a special paint which is designed to last only for up to 1 year. After this time the pictures will fade. Of course they could be protected like icons in a temple. However they can also be looked at and we can observe how they slowly and systematically become less and less visible, to become in the end only a memory.

The project’s motto are the words of Hanna Arendt: “There is no such thing as forgetting; at least one person will always stay alive in order to pass on the record.” Kowalewski pays attention to what exists beyond the visible spectrum and at the same time emphasises that despite the fact that those tragic times have been spoken of many times and in many different ways, that due to its subjective nature, memory always has many histories still to tell.

For Kowalewski the pretext for this approach to an unusual dialogue with history and memory was the fate of his mother, Zofia Jastrzebska, as well as the mothers of other of his friends. The artist opens a new perspective. By the presentation of women who experienced unimaginable horrors, he manages to show their extraordinary beauty, strength and courage, and he shows that it was in fact these very traits that led to a large extent to their salvation.

The history of polnische mame has also become a pretext to talk about the generation which is now leaving us, a generation which formed us – the people who currently are the strength of the World. The women whose history are shared, and whose portraits are exhibited, have become in a way a symbol of a whole generation, women who threw off their past youthful experience of totalitarianism so as to normally function in society. Irrespective of where they happened to come to live later. They have now lived their lives and have disappeared from our world, leaving behind them memories which become even more precious as they have left us. It is our duty to cherish this legacy. This memory of a person or time which we carry in ourselves, in our beating hearts. Nothing can change this. This is the strongest indicator of our heritage, though invisible and inaudible. But it is still there; just as a Genotype.

Paweł Kowalewski about inspiration for the exhibition Strength and Beauty:

In May 2012 my 89 year old mother, an energetic and brave woman who had fought for the Home Army during the Second World War, a charismatic, strong and brave woman with a very strong character – suffered a heart attack. The heart attack resulted in a lack of oxygen getting to the brain which in turn meant that during the last 20 months of her life she unexpectedly changed into a joyful, warm person, almost like a helpless child. She displayed a warm and frivolous sense of humour, with her memory working a bit like a camera, summoning up images from the past. There were various scenes, sometimes joyful, sometimes tragic, and almost always related to the times of her youth.

In 2011 I received a fantastic birthday present. My closest family bought me the medical test, 23andMe. In addition to many very interesting facts about my health, it also gave me information about my background. It turned out that more than 13% of my genotype came from the Ashkenazi Jews. During the last 20 months of my mother’s life I decided to check whether the 23andMe tests really confirmed my family’s intuition about our ancestors, emigrants from Hungary. As a result of this, after a further set of tests, my mother discovered that more than 26% of her DNA was an Ashkenazi genotype.

I decided to share my reflections about my mother with my friends – Jews, citizens of the state of Israel. People who had either emigrated or had been forced to emigrate from Poland. During our discussions we all came to the conclusion how similar to each other our mothers were! From conversations, memories and fragments of their personal history the first similarities began to slowly emerge. They were all beautiful and strong. With an extraordinary awareness of some strange curse with which they were filled. All of them hiding in their interior worlds behind a facade of beauty the traumas of the youthful, wartime years in which they were given to live.

The stain of totalitarianism, the bloody demons of the 20th century had influenced to a greater or lesser extent their whole lives and had determined their characters, behaviour and attitude to reality. These brave women, living in Poland, Israel and the United States later became mothers, wives, lovers and in many senses pillars of our everyday existence. Today they have gone. In our memories they remain as strong, uncompromising creators of our realities.

My mother was a beautiful woman. Tall, with blond curly hair encompassing her face, a wonderfully protruded chin and a magnetic look. Perfectly dressed. Looking after herself with great solicitude, always with her nails done and lipstick on. Beautiful till her last days. It was she who first taught me what beauty is – although often completely subconsciously, as a by-product of the everyday – even in the smallest things, like shared meals. The table had always to be elegantly set, and the dishes carefully prepared. Beauty, even in the difficult times of war. With an enormous appetite, to love and to live.

Just behind her beauty that was visible at first glance, came a force which was not often easy for her loved ones to bear. A dominating woman, with a powerful character who brooked no dissent, with a tendency to exaggerate in her care for us. Tenacious and extraordinarily brave when it came to defending the values in which she believed. Generous. Ready to risk her own health for others, and even her life.

I’d always been aware of my mother’s beauty. But it was only recently that I started to ask myself the question of what lies behind this beauty. Did she know she was beautiful? Did it give her strength? How did it influence her life? What was hidden behind this beautiful face? I started to observe it from a unique perspective. Using some strange sense to peek under the covers of her universe.

As an artist I felt that I had to make my voice heard in this situation and I couldn’t allow that this experience that had so affected me (and those closest to me) would remain without commentary. My whole approach to art is a consequence of my vision of art as being personal, and private, art that perceives the world through the soul and mind of the artist. My art is therefore a continual search. In this way the idea for the exhibition Strength and Beauty. A very subjective history of Polish mothers was born. As an artist I believe that art must challenge, it cannot bring calm, it should speak of what is insoluble. And beauty of whatever kind is always extremely stimulating.

Stories of portrayed mothers from the catalogue accompanying exhibition:

Zofia Jastrzębska (1923-2014)

The hospital was crowded. There wasn’t much space, so some of the injured lay on temporary mattresses which were made from anything to hand on a dirty and bloody floor. Zofia was lying by one of the sticky walls, which was liked by many of the passing flies. They had removed most of the shrapnel left by German grenade, the biggest danger was therefore gangrene, which was highly likely to get into the large wound on her forearm. If by the next morning the infection had increased then she would face immediate amputation.

She started to pray – harder than ever before – asking God to save her from becoming an invalid. It was enough to look around her to know that many of those whose wounds they had somehow managed to cure would however be permanently disabled. All through the night in the hospital one could hear screams and moans, and from outside came the blast of explosions and shots. Despite the pain she finally fell asleep thanks to the dose of morphine.

A doctor awoke her while doing his morning rounds. He had already looked at the wound and had a ready diagnosis – what an extraordinary coincidence! During the night or a bit earlier flies had left their larvae in the wound and by feeding on bacteria they had cleaned it, thus eliminating the risk of gangrene. Amputation wouldn’t be necessary after all.

Although her arm didn’t regain its previous dexterity for the rest of her life Zofia was convinced that that day she had witnessed something more than an extraordinary coincidence!.

Blanka Amsterdamer (1918-1998)

She started to speak – or rather throw out individual words. Her fear suddenly disappeared, her concerns diminished and each sentence led as if automatically to the next, lending even greater credibility to her display of anger and aggression.

…What is the meaning of this! – she shouted at the increasingly unnerved private in his shabby jacket. As she was lightly pushing the intruder back with each blast of her inexorable invective, they quickly reached the door. Retreating, the disorientated blackmailer crossed the threshold and Blanka slammed the shop door shut behind him with all her strength. With such force in fact that she was even afraid that she had damaged the frame and that the door now wouldn’t close property. Through the closed door the man heard some further insults until he finally departed. So was it ok now? As soon as he left she collapsed onto a chair, suddenly losing her strength. Before fear came, for a moment she still felt fury and outrage!

He had tried to tell HER that she, the owner of an antique shop open 5 days a week in occupied Warsaw is a Jew!

HER! -with her Aryan papers which up to now hadn’t caused even a flicker of doubt with even the most seasoned officer.

HER! – with her features, faultless Polish pronunciation and long fair hair falling onto her shoulders.

HER – Blanka Amsterdamer!

However, when later that day she returned home she didn’t feel so certain any more. The foundation on which she had built relative stability seemed to be much less solid. Her papers suddenly seemed less authentic, her features less Polish and her hair less blond. She cursed again under her breath. She wanted to see whether it sounded as natural as when it came out of the mouth of her fat neighbour from the second floor. It didn’t. Tomorrow she would open her shop again. As usual.

When would this end?

Anna Goldburt (1920-2007)

It’s completely dark and silent in the camp. Anna can clearly hear every rustle of leaves – even from a distance. Only the forest, lit by moonlight and shaken by the wind lays more and more shadows on the path, making her observation more difficult. She knows this forest so well that it doesn’t awaken her fear anymore. All her concentration is on the dark and narrow path – the only one which you can use to get here by horse. Bad feelings mix with the good – he’s sure to be alive! He’ll definitely return!….And if not?

She’s been waiting a long time and each minute seems to last an eternity. Each noise, each rustle, of which there are always many in the forest, gives hope that soon she would hear the familiar clopping of horse’s hooves. Normally however it was just a deer frightened by its proximity to the camp or simply a dry branch which the wind had broken off the main part of a tree. She sat there still for a long-time, frozen, frightened, ripped apart by conflicting emotions of sadness, hope, anger and yearning.

Suddenly something moved between the trees and after a moment in the distance appeared the silhouette of a man on horseback.

It’s him! – she thought – it must be him!

She ran towards the figure however when they were nearer each other she noticed that he was moving differently than normal. He was in a strangely hunched position and the horse was carrying him submissively, as if by instinct.

Anatol! Anatol! –she cried out, a bit louder than she should have in the middle of the night in a partisan camp. But Anatol didn’t answer. For that short moment, Anna felt as if her heart really had stopped beating in her breast.

He’s injured! Maybe seriously? Maybe fatally?

The rider slowly and clumsily collapsed onto the ground. Anna threw herself towards him, pushing the horse aside so that he no longer blocked out the few rays of moonlight which had managed to get past the cover of the trees. She quickly took him in her arms and lifted his head. Suddenly she felt the strong smell of liquor, distilled no doubt in a neighbouring village. It wasn’t difficult to find hard liquor and women’s company there. Again she felt mixed emotions, love and contempt, caring and a feeling of hurt. She laid him down so he could sleep, but she wasn’t able to sleep herself. Like before on the path when she imagined to herself his tragic fates, her thoughts didn’t give her any peace. Who had he been with? Why had he been so long and why were his shirt buttons not done up straight?

Fela Levinsohn (1920-1969)

In the kitchen it was cold, but quiet and cosy. It was the kind of silent, peaceful and slow moving evening which most favours reflection and contemplation. Father was just brewing some tea when suddenly they heard a characteristic and firm knocking at the door. It wasn’t difficult to tell the difference between the knocking of your neighbour or a door to door salesman and the knocking of the all powerful services of the state – particularly during the occupation.

For a moment they looked at each other without speaking. Finally Fela gathered up all her courage and moved towards the door. With the Gestapo there would be no negotiation, but if it was the Police they normally agreed to waive their procedures in return for some valuables or a little cash. There was a deathly hush in the flat. She could hear her own heart pounding as she turned the handle. She opened the door and seeing Police uniforms sighed with relief. She knew that probably nothing worse awaited her than the loss of some of the money which she had managed to save and hide up to this moment. She wasn’t wrong. The negotiations didn’t take long. The uninvited guests knew very well to whom they had come and why, and she had learnt how to deal with such situations. This time she managed.

After she had paid the agreed amount and finally closed the door, peace and quiet reigned again. She was angry that she had lost some money, but at the same time proud that she had single-handedly managed to see off the danger at least for some time. She went slowly to the kitchen to finish her tea and tell her father about the details of what had happened, as he may not have heard everything through the closed door. She looked at the table on which the mug was still brewing. He was lying beside it. His head on the table, completely motionless. Dead.

Fear works fast, similar to the cyanide which he’d bought when they’d taken mother to the Camp. He’d promised himself that he wouldn’t share her fate. But it hadn’t been the Gestapo.

Irka Malin (1916-2000)

The Germans were already in Warsaw. In the flat everyone was listening to the radio and Irka was looking at the suitcases, battered by many difficult journeys. Those same suitcases which as a 14 year old she had helped Mama pack when they left to settle in Palestine. The same ones with which she left when she returned to Poland at the age of nineteen after some of the local Arab population threw stones at their house and they felt less safe.

Now a mere 4 years later, she is packing them again, even though she had in fact only just settled in properly. Now the contents were restricted only to essentials. Excess luggage could create a serious problem in this journey. This time it was no longer a departure but an escape! Although, in fact, which of those departures hadn’t been an escape?

She sat on the suitcase so as to close it and remained there for a moment. She didn’t know when she was going to be able to sit for a moment again.

Helena Miodownik (1914-1999)

The camp in Kazachstan was overcrowded and constantly suffering from a shortage of food, which led the inhabitants – including Helena – to suffer in extreme moments from strange body reactions, such as apathy, comas and changes to the skin or swelling. Everything that happened there had consequences for one’s health, however her son’s symptoms might only turn out to be a fleeting infection. A light cough, greyish deposits around the throat – could be nothing, but for her, a nurse with many years of experience, she knew from the very beginning that there were many potential scenarios.

During her many years of work with the sick and injured she had learnt how to deal with omnipresent pain. Almost every morning when coming back from her shift she would see an empty bed, where the evening before a patient in a critical condition had lain. Despite the desperate pain, fevers or breathing difficulties whenever they had a chance they told of their children, wives and the places where they came from. She had learnt how to live with the awfulness which came with the hunger and extreme conditions in which they lived – it was what her profession demanded – although caring for one’s own child was something completely different.

When she came back from her shift in the evening, her son was feeling worse than in the morning. The symptoms hadn’t lessened and the grey deposits in his throat had started to mix with brown blood. It was diptheria.

The symptoms worsened day by day. Helena now knew that she wouldn’t be able to get the necessary medicines and she wouldn’t be able to ensure him the care he needed – even though she worked for the local health service. Quickly all her hope disappeared – even an uneducated person who was not aware of medical issues would know quickly that such a small child, weakened by a lack of basic nutrients would not be able to deal with such an illness. She spent the next days at home, looking helplessly at the suffering of her own son – a small defenceless child, who was losing his strength, and was fighting more and more for every breath.

He couldn’t even tell her a moving story or state his yearning for the beauty which had given him life. He was too small and he only knew hunger and pain. She felt so helpless as slowly she lost the only treasure that she had left on this earth. The world would never be the same again for her.

Fanka Igel Shechter (1907-2000)

She came to the work camp near Vienna thanks to bought Aryan papers in the name of Janina Czajkowska. No-one there even for a moment suspected that she and her children might be Jews. Her perfect knowledge of German from her studies in Lwow and the ease by which she made new contacts meant that she could operate in her new surroundings with a lot of freedom and considerable self-confidence.

She managed so well that shortly after arriving she organised a meeting with the camp commander. She was hoping that her knowledge of German would help her persuade him to improve her children’s living conditions at least a bit. She was still standing by the door when the officer heard how fluently she spoke his native tongue and he immediately decided to send her to a comfortable position as a translator in the nearby Arbeits Amt. The fact that she knew German, Polish and Russian turned out to be a valuable asset, although she felt that her beauty was also a factor. Feeling even more confident she decided to go one step further.

Unfortunately this isn’t presently possible Herr Leiter! – she replied after pretending to consider the matter for a moment. – Arbeits Amt is far from here, and I don’t want to leave my children for so long without care. However if Herr Leitner would allow us to be quartered outside the camp, near to my new work place I would consider the proposal.

Even more intrigued by the beautiful, eloquent and forthright Pole, the commander agreed without further thought, and from this moment she together with her children lived a relatively peaceful life living in the house of a respected Austrian burgher right in the heart of the Third Reich. Only the frequent transports from Poland made her feel uneasy. She was afraid that as a translator she would eventually come across someone she knew, who on seeing her would suddenly shout out Fanka! Nothing like this ever happened though.

Matl Szpigelman (1907-1998)

Stanislaw dropped by that evening which was not unusual. They had been friends for years and even in these difficult times they helped each other as much as they could. Indeed the flat in which they had spent the last couple of months belonged to Stas; he had allowed them to stay there so that it would be harder for the neighbours to ask any questions. He was always very helpful and could be relied on.

She was happy when he paid them a visit. Maybe this was not the best time because the little one had been sick for a good couple of weeks and the situation in the city was so difficult that there was no way of getting the medicines he needed. But it was the 4th year of the war after all. A little mechanically she gave him a cup of coffee which she had made earlier and offered him a seat. She only then noticed that he was as white as a sheet. When he then asked them to move out because it was creating too much danger for him, she must have looked even whiter herself. She took a moment to gather herself, but as soon she had taken in the full seriousness of the situation she understood that she had to defend herself immediately. She must fight for her life, here and now in the middle of the kitchen.

She fought with the only weapon she had, her weakness and desperation even though Stas was implacable. He too was fighting, for his chance and for the future of his family. He had learned too much from the years of occupation, experienced too much, played the hero for too long for there not to be a risk that one day he would crack and lose his nerve. Today was that day.

They shouted at each other and later talked more quietly, until one of them raised their voice again when their emotions got the upper hand. Yet despite being in such a hopeless situation she didn’t give in. After all, she wasn’t about to start moving out right now carrying a sick child!

Either we stay put or the Gestapo will have to force us out! – she shouted when the situation really seemed to be getting desperate. Her voice was shaking, her legs and arms seemed to have stopped responding as a result of her desperation. – It comes to the same thing, as anywhere outside of this flat the same fate awaits us!

Stas started to cry and then left. His cries from outside the flat soon went silent for a moment. She collapsed into a chair and only then did she allow herself some brief tears.

Stanislaw didn’t go to the Gestapo. Maybe he was afraid that despite his denunciation he could still face consequences for having hidden Jews? Or maybe he was simply a decent man?

Zapora Trachtenberg (1918-2012)

Staring at the window, Zapora, sick with worry, waits for her parents who together with her three brothers had gone out for a walk and to do some shopping.

She hadn’t felt like going out today. She preferred to stay at home. She liked its calm atmosphere – even now during the war. But this house was Them; Mum, Dad and her brothers, who even though they often teased and annoyed her also ensured joy and liveliness, emotions which now in this empty house she missed more than ever before.

She wanted to feel safe, cuddle up to Mum, and feel the presence of Dad, who was always able to solve any family problems. But she’s also furious with them! Why are they taking so long to come home, so that her thoughts go crazy, going over and over the worst possible outcomes? They should have been back hours ago. But maybe not? She hadn’t been listening too closely to what her Mum had said when she went out. She was too busy reading.

Time passes and the shadows on the streets get longer until finally dusk comes. Now you can only see fragments illuminated by a few yellow street lamps. There are still no five silhouettes to be seen, each of which she would recognize by their walk, clothes and posture. There is just an empty, quiet house in which with every passing moment there is an even bigger nobody.

She never thought that house can be so empty, but on the other hand she never even imagined that someone can lose all loved ones at one day.

Halina Zingel (1930-2004)

From far you could already hear it coming. The rhythmic knocking started to slow, and the arrival of the train transformed it into a deafening screech. When the train finally came to a halt and the noise abated, on the platform there was immediately a commotion. Only a moment passed before again there was an unbearable din, especially for a 9 year old girl.

Halinka wasn’t completely sure what they were doing. She was supposed to be going to Siberia – even-though she had no idea where this was or what would become of her there. Perhaps, like children do, she was more concerned with other matters, like being tired and the fact her uncomfortable shoes had been rubbing her feet since she left home. She had even wanted to tell Mum about it, but she was too busy giving out instructions and keeping an eye on the luggage.

Everyone was running this way and that, families saying farewell, shedding tears, and making promises to each other. Sometimes she fell under the feet of some hurrying passenger, but luckily it was never anything serious. When she was already standing on the carriage steps, suddenly somebody grabbed her hand and started to pull her back to the platform – it was her sister. After a moment however a second stronger hand started to pull her back in the direction of the interior of the carriage – it was her mother. Both of them were shouting something to each other over her head. Just then she was barged again by someone dragging a suitcase up the carriage steps and trying to squeeze between the two women.

Be careful! Mum scolded the man, and then went on shouting to her sister about something Halina didn’t fully understand.

Children have to be with their mother – she catches and she can only agree with this idea as a 9 year old “Mummy’s girl”. But she loves her sister too. She likes playing with her and listening to her stories – eventhough she is much older.

Finally one side lets go. Mama pulls her up higher, one step at a time, until finally she is inside the wooden panelled carriage. Disorientated, she waves to her sister, as if she was saying goodbye only for a moment.

That was the last time she ever saw her, but if she had stayed with her sister she would almost certainly have also not survived the war.

Juliusz Windorbski – portrait

lenticular printing, limited series

2021

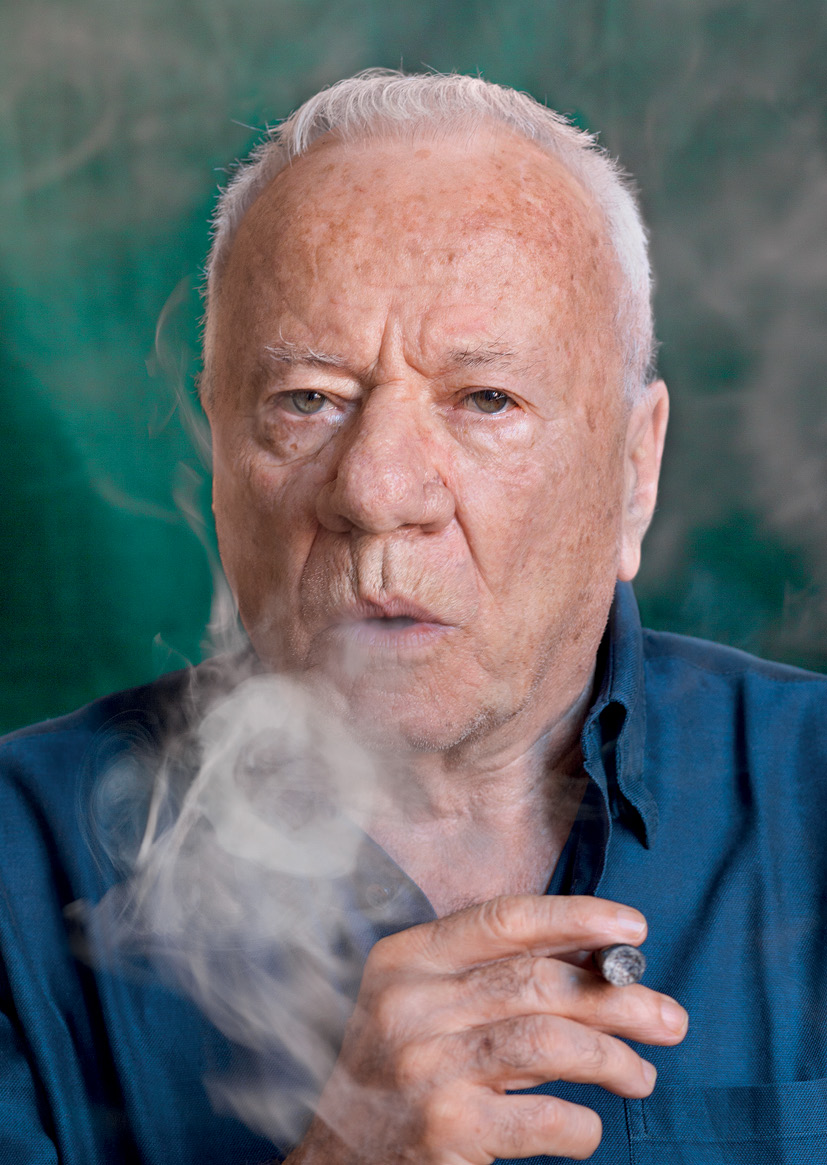

Achille Bonito Oliva – portrait

lenticular printing, limited series, nowadays exhibited at Castello di Rivoli Museo d'Arte Contemporanea in Italy

2019

Anda Rottenberg – portrait

lenticular printing, limited series

2018

postcards from cycle "Not Allowed!", performance during the Biennale in Venice

2011

Do not Rush

2012

Do not Rush, (lightbox, 82 x 125 x 12 cm)

2012

No Weapons Allowed

2012

No Weapons Allowed, (lightbox, 43 x 64 x 12 cm)

2012

No Weapons Allowed, (lightbox, 43 x 64 x 12 cm)

2012

Wrong Way

2012

Wrong Way, (lightbox, 82 x 125 cm)

2012

Europeans Only

2012

Europeans Only, (lightbox, 150 x 200 cm)

2012

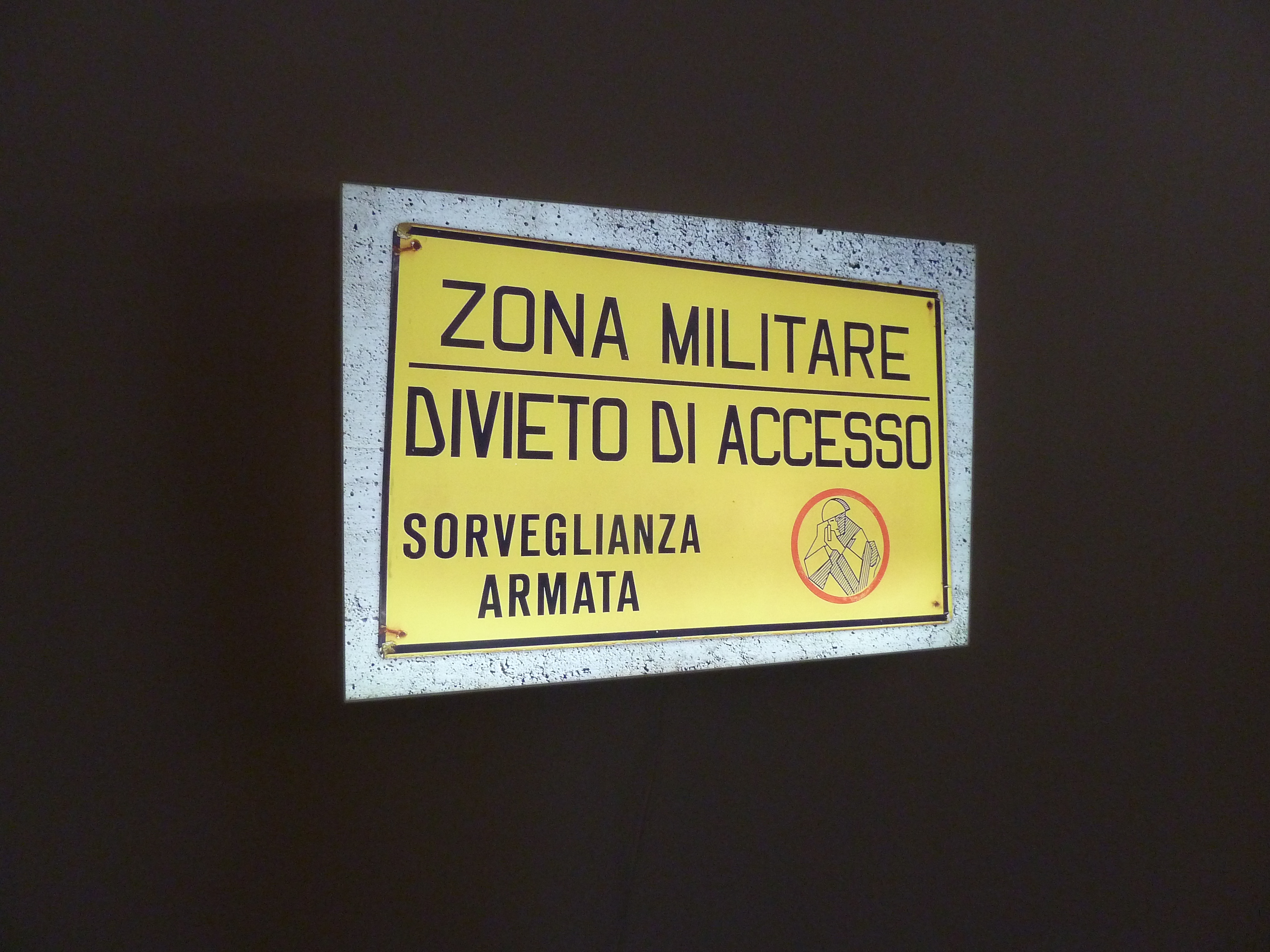

Zona Militare

2012

Zona Militare, (lightbox, 82 x 125 x 12 cm)

2012

Zona Militare, (lightbox, 82 x 125 x 12 cm)

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, Propaganda gallery

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, Propaganda gallery

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, Propaganda gallery

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 1

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 2

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 3

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 4

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 5

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 6

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 7

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 8

2012

Totalitarianism Simulator, fragment 9

2012

Strength and Beauty – Zofia (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015

Strength and Beauty – Blanka (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015

Strength and Beauty – Anna (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015

Strength and Beauty – Fela (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015

Strength and Beauty – Irka (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015

Strength and Beauty – Franka (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015

Strength and Beauty – Matl (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015

Strength and Beauty – Zapora Gołda (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015

Strength and Beauty – Halina (offset print on dibond, 200 x 140 cm)

2015